by Sheren Javdan

April 17, 2014

General Mills, Inc. consumers are hesitant to download coupons or interact through social media with the company. General Mills Inc., a Delaware corporation, is the maker of large brands such as Cheerios, Bisquick, Betty Crocker and Pillsbury.

The New York Times first reported that General Mills has added covert language to its website policy terms. Per the article, the language alerts users that by liking their Facebook page, downloading coupons, or entering company-sponsored sweepstakes, they are barring themselves from bring forward a legal suit.

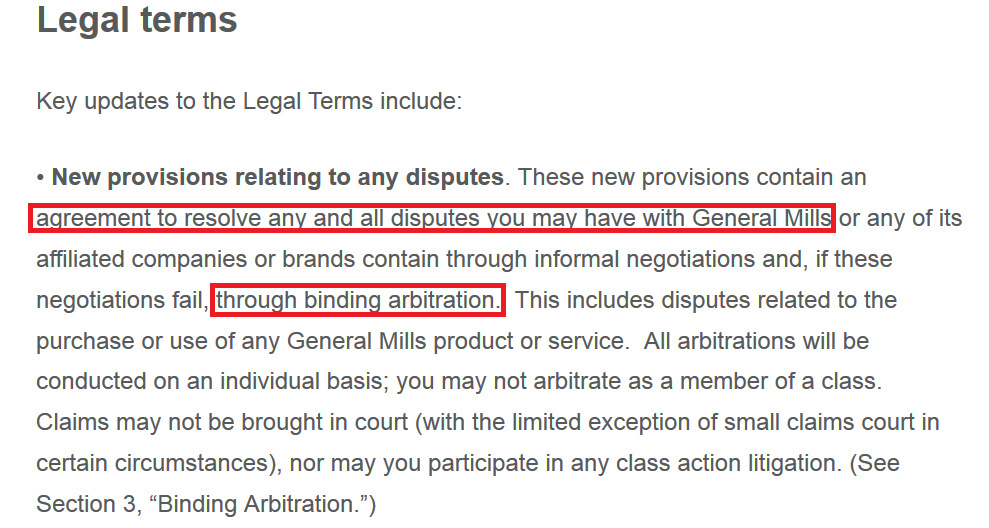

Here is an excerpt from the General Mills website:

After being contacted by The New York Times, General Mills further suggested that merely purchasing its products would bind consumers to the policy terms.

The fine print notifies consumers with legal issues or disputes that they must first submit their claim through an informal negotiation via email. Should the informal negotiations fail, consumers should seek out relief through binding arbitration.

Arbitration is a form of resolving legal disputes outside the traditional courtroom. Most contracts to which parties have agreed to include an arbitration clause. Parties involved in a dispute submit their claims to an arbitrator, an unbiased individual, who will listen to the evidence and make a decision.

Unlike a courtroom hearing, arbitration is less formal and the arbitrator may base his or her decision on their personal idea of what is fair and just. The law or earlier cases do not bind arbitrators.

Furthermore, an arbitrator’s decision is generally final and very difficult to appeal.

General Mills consumers showed outrage as the news meant that individuals injured by the products could no longer sue the large company in the courts. Children suffering from allergic reactions to an ingredient not listed on the ingredients list would be left to arbitrate in front of an arbitrator.

When initially asked for a comment, General Mills representatives denied. Thursday, after The New York Times article was published, Mike Siemienas, a company spokesman, issued an email stating the “online communities” referenced in the policy terms are only those “hosted by the company on its own website.”

A second email informed The Times that nobody is prevented from suing merely through the purchase of General Mills products or liking of the brand on social media sources. “Should an individual subscribe to one of our publications or download coupons, these terms would apply. But even then, the policy would not and does not preclude a consumer from pursuing a claim.”

The email goes on to explain that the policy terms only determine the forum in which the claim may be pursued. Furthermore it states, arbitration is a “straightforward and efficient way” to resolve any claims.

Many consumers have taken to social media to express their outrage over the new policy terms. Some consumers have even gone as far as to boycott General Mills.

Many consumers also find the policy terms unconscionable. Contracts and agreements are found unconscionable when the terms are so shocking and unfair that they cannot be allowed to stand.

Because General Mills, a multimillion-dollar corporation, has an unlimited source of resources and the ordinary consumer has so much less power, there is grossly disproportionate bargaining power in the policy terms.

If the arbitration clause is found to be unconscionable, the court may either void the agreement and make it unenforceable, or choose to only enforce the conscionable portions of the policy.

Regardless of whether the policy terms are actual enforceable, the media buzz surrounding General Mills has instilled a fear and hesitance in consumers.

Topics: Facebook, General Mills