Hackers have demonstrated how simple it is to wirelessly gain catastrophic control of a vehicle's accelerator, brakes, steering & transmission, over any cellular network. An estimated half-a-million vehicles are currently exposed.

by Brent Lightfoot

July 24, 2015

Do you ever spend time thinking about where or how the next terrorist attack against the U.S. will occur? I really hope not, because it might indicate some acute, undiagnosed paranoia. Sometimes I worry about it, but people like me don’t sleep very well.

I only raise the question because, this week, two hackers publicly demonstrated that they could take control of the cyber system of a Jeep while it was running on the highway. A run of the mill Jeep. A Jeep outfitted with the same cyber system that most of our cars run on now.

And it led me to think, maybe the next terrorist attack, if there is one, won’t be from the sky. It won’t be from the sea. Maybe it will be our own cars that are attacked, while we are driving them.

The Internet of Things

The problem begins with interconnectivity. We live in a world today characterized by the Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT denotes the infrastructure of manufacturers, operators, and connected devices that exchange data with other connected objects through a network of embedded electronics, software, and sensors.

Examples of objects within the IoT are smartphones, tablets, laptops, airline flights, dating apps like Tinder, nanny cams, smartdolls like My Friend Cayla, and even refrigerators. The IoT is ingenious in that it allows us to maintain connectivity amongst disparate objects across distance.

However, the dark side of the IoT is its vulnerability. All of the examples listed above have been shown to be “hackable” and, thus, controlled by third parties. In effect, the most quotidian of devices is prone to third party seizure and control, maybe from half a world away.

As the Washington Post noted in a recent article, the vulnerability of the IoT is nothing new. For instance, in 2007, then Vice President Cheney had the wireless connectivity in his heart defibrillator disabled in fear that terrorists could hack the device and send him into cardiac arrest during an assassination attempt. (That was paranoia.)

Then, in 2009, Israeli and U.S. intelligence hacked into Iran’s nuclear centrifuges and uploaded malware onto them, causing them to spin wildly out of control and into dysfunction. In 2011, a trio of security researchers (the “good” hackers) hacked into the system controlling prison doors to open and close. In effect, it has been clearly demonstrated over the last ten years that mechanical systems are vulnerable targets.

Automobiles became targeted soon thereafter. In 2008, a 14-year-old in Poland seized control of the tram system in Lodz, Poland’s third largest city, using a modified television remote control. Then, in 2010, a 20-year-old disgruntled ex-employee hacked the Texas Auto Center in Austin, using an Internet device implanted in the dashboard of their cars to gain control of customers’ vehicles and blare their horns in the middle of the night. (The next morning the cars wouldn’t start.)

Drones are another popular target. For instance, an American Sentinel drone disappeared into Iraq in 2011, and the Iraqi government claimed its cyberwarfare team had taken control of it. (Subsequently, Iran told the press that it had possession of the drone’s video footage.) Then, in 2013, hacker Samy Kamkar reconfigured a commercial drone into a hack-mobile capable of locating and taking control of other drones as they flew nearby. Kamkar claimed that, if enough drones were in the sky, a user of his system could control of “an army of zombie drones” from their smartphone.

Kamkar told the Washington Post that he has determined how to hack remote-controlled garage doors, as well as “pretty much… every car” he’s looked at. Using the locking system, Kamkar claims he can infiltrate any vehicle using a code he has written. Kamkar explains that this is possible because most automakers buy hardware from the same suppliers. The unlocking systems tend to utilize the same radio frequencies. Cracking them means that any car using them is yours to control.

The Jeep Hack

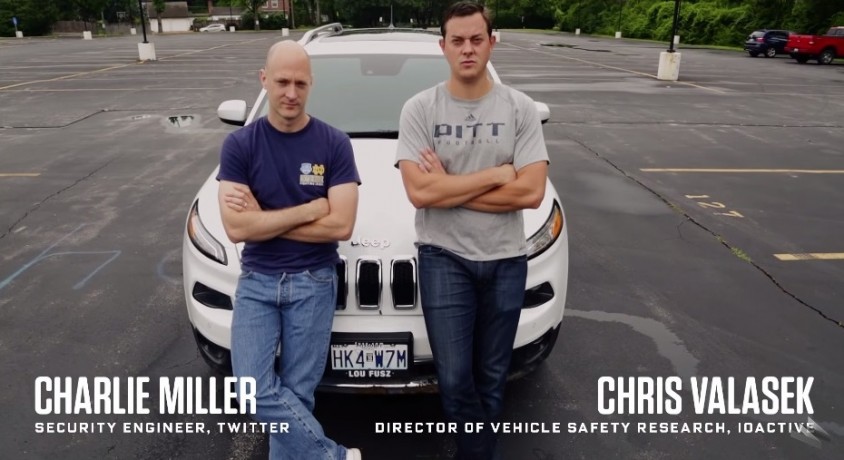

Basically, cars today are “smartphones on wheels.” As such, they are just as vulnerable to hackers as your smartphone. Recently, Wireless writer Andy Greenberg volunteered to subject his car to remote controlling by hackers while he was driving. Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek, both professional “security researchers,” seized control of Greenberg’s Jeep Cherokee while he was driving on the highway around St. Louis.

They started blasting cold air from the vents on the dashboard and bumping the local hip-hop station on his radio (Skee-lo was probably the right thing to be listening to at the moment). Greenberg couldn’t alter the controls from inside the car. The windshield wipers turned on and spit cleaning fluid onto the glass. An image of the two hackers in track-suits flashed on the Jeep’s digital display, mocking the driver.

Via Wired.com

The hack didn’t stop there. The two security researchers proceeded to cut the Jeep’s speed in half. Greenberg, jumping on the gas, couldn’t get the car to accelerate at all.

Previously, the team had demonstrated to Greenberg that they could disable the breaks, honk the horn, jerk the seat belt, and commandeer the steering wheel. When Greenberg’s article was published earlier this week on Tuesday, July 21, the media, online and mainstream, went crazy. The vulnerability of ordinary vehicles to wireless hacking and third party control had been exposed.

The Door In

As smartphones on wheels, cars today have IP addresses just like any computer with an Internet connection. Miller and Valasek say that the IP address provides the doorway in to taking over control of all the systems in a vehicle. The two security researchers say that they can take over any 2013, 2014, 2015 model.

Greenberg’s Jeep uses a system called “UConnect” for information and entertainment (thus, infotainment). UConnect utilizes cell service to provide driver services like “Vehicle Finder, Send Destination to Vehicle, a Monthly Vehicle Health Report, and Vehicle Health Alert.” Telematic units like UConnect derive from the original General Motors system, OnStar, and they are commonplace in today’s vehicles. They all operate according to the same basic principle, using cellular signals to locate vehicles and send information to the car’s computers.

Sprint was the cellular network operator for Greenberg’s Jeep. Network operators can help to block access to the car’s cellular connection from third parties, but it may or may not be economically feasible for them to allocate the resources to do so.

Even if they did, there are numerous sites of connectivity within cars matching the number of computers in place within the vehicle hardware (up to 40 in certain car models like the Toyota Prius or the Range Rover Sport), so cellular security only addresses one access route for car hackers. The access point could come from Bluetooth technology, radio data systems, or onboard WiFi networks, in addition to cellular connectivity.

Once inside, a hacker can commandeer the adaptive cruise control, collision prevention, or lane-keep assist systems that send signals to the steering wheel, accelerator, and brakes.

Regardless of the point of entry, Miller and Valasek’s cellular hack is compatible with all Fiat Chrysler motors, including Ram, Durango, and Jeep models, since 2013.

What’s even more alarming, telematics systems akin to UConnect pervade the automotive industry today, including GM Onstar, Lexus Enform, Toyota Safety Connect, Hyundai Bluelink, and Infiniti Connection. What it means, is that Miller and Valasek’s method could be utilized in almost every car make and model since 2013.

Implications: Legal Liability and Legislation

The idea that someone could take control of your car from a remote location while you are driving it is terrifying. Two U.S. Senators have recognized this and, on the same day Greenberg’s article was released, they introduced legislation establishing national safety and privacy standards for vehicles on American roads. The plan also proposes a rating system for gauging vehicle security from hackers.

The legislation, proposed by Edward Markey (D-MA) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) is called the Security and Privacy in Your Car (SPY Car) Act. If adopted, the plan would require the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the Federal Trade Commission to set out security standards for critical systems like steering and engine power, in an effort to prevent remote hacking and control.

Coming into effect two year after adoption, the legislation also levies a $5,000 fine for any breach of the security standards. Finally, the SPY Car Act would establish standards for protecting consumers’ privacy as well, creating a “cyber dashboard” rating system informing buyers of the vehicle’s protection against hackers.

According to Kathleen Fisher, a Tufts University computer science professor and security researcher, the problem is systemic in the automotive industry because car manufacturers don’t have the right incentives to address the issue on their own. Because care buyers typically pay for what they want now and not to avoid theoretical future calamities, the manufacturers rarely compete in terms of interface security. Thus, they will need some governmental prodding to correct the security flaw.

If the federal government or insurance doesn’t force automakers to address the problem, another potential salve could be in the courts.

A Texas lawyer has already filed suit in a San Francisco federal court seeking recovery from various automakers for cybersecurity flaws (he had seen a “60 Minutes” report illustrating the ability of hackers to overtake cars).

However, Jonathan Zittrain, a Harvard law professor and director for the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, suggests that physical injuries would makes suits against automakers for cybersecurity flaws stronger. Zittrain foresees the invocation of tort law leading to large damage awards based on the actions of a company causing harm to consumers. “If my heart monitor fails and I die as a consequences, the company can’t say, ‘Oh it was only software,’” said Zittrain. “That’s no defense. That’s not going to fly.”

Other legal issues include cyber security researchers, the “good” hackers, needing access to copyrighted code in order to test it for vulnerabilities without fear of legal recourse by automakers.

Don’t Freak Out Yet

At this point, it would probably be premature to move into the wireless bomb shelter in your backyard to hide out for the next couple decades. As John Ellis, a former global technologist for Ford, pointed out, “[the hackers] haven’t been able to weaponize it. They haven’t been able to package it yet so that it’s easily exploitable. You can do it on a one-car basis. You can’t do it yet on a 100,000 car basis.” And, just as was done with drones following the exposure of security flaws by benign hackers in 2013, the code in vehicles could be strengthened by automakers to prevent the possibility of attacks.

If you are concerned about the security of your Jeep or any other vehicle, look to your automaker for a software fix.

Chrysler Fiat has just issued a recall and provided an update that you can upload onto your car system using a flash drive that they will provide. The company is calling the recall “an abundance of caution,” as no actual injuries have been reported in relation.

The recall actually covers more models than those initially identified as needing the patch, including 2015 Ram pickups, Jeep Cherokees and Grand Cherokee SUVS, Dodge Challenger sports coupes, and Viper supercars. Given the widespread use of such vulnerable infotainment systems, other companies are sure to follow.

More or less, it looks like we are still safe. Your refrigerator is just as liable to be hacked as your car. What’s point in losing sleep about a stalling transmission or souring milk?

Be aware, not worried. Sleep tight, and let the security researchers do their jobs.