Will Amazon’s revolutionary patent redefine shopping?

by Jonathan Schmig

April 10, 2015

For months now, rumors of e-retail giant Amazon’s plans for a brick-and-mortar initiative have been murmured throughout the retailing world.

Amazon was supposed to have opened a store in Manhattan in 2014, and it was apparently considering the purchase of hundreds of Radioshack stores as well. Neither of those plans materialized. (At least not yet.)

Amazon has already experimented with a variety of shopping mall kiosk setups and college campus bookstores, but those ventures have been extremely limited in scope.

Now, however, according to recent patent filings with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Amazon may be pushing forward with its brick-and-mortar plans after all.

In a patent filed last September and obtained in January, Amazon outlined its plans for a process whereby shoppers could exit a retail store, items/groceries/gifts in hand, without ever having to stop at a checkout station or interact with a cashier.

The application adds that this system could also be used in warehouses, and in a variety of other “materials handling facilities,” including libraries, rental stores, and museums, showing that “purchases” are not the only transactions contemplated by the patent.

Essentially, in a store that has implemented this system, consumers can shop as normal—examining items, taking their time, comparing name brands to generic brands, etc.—and then, simply, walk out.

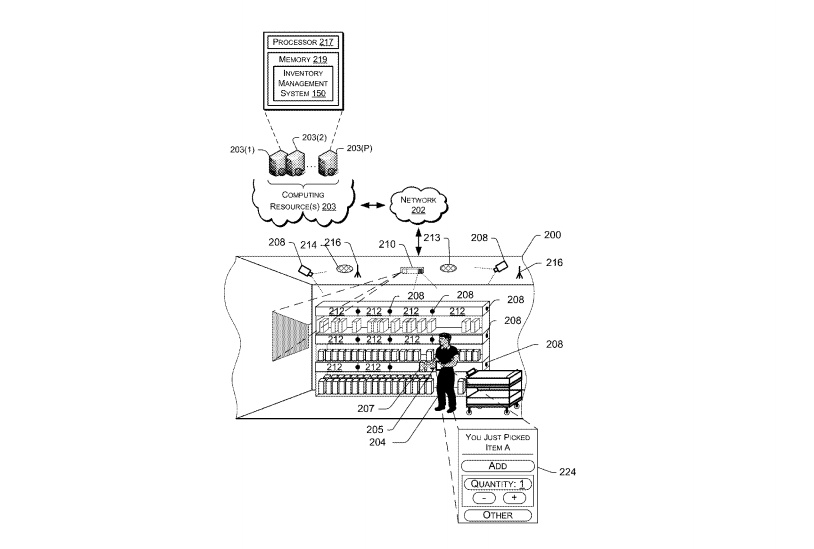

Behind the scenes (or from above), cameras and sensors would be taking diligent notes and analyzing images as the various consumers go about their shopping.

An illustration from Amazon’s patent application

“For example, an image capture device (e.g., a camera) may capture a series of images of a user’s hand before the hand crosses a plane into the inventory location and also capture a series of images of the user’s hand after it exits the inventory location. Based on a comparison of the images, it can be determined whether the user picked an item from the inventory location or placed an item into the inventory location,” says the patent.

This could mean not only the end of cashiers, but of shopping carts and bags altogether.

When a shopper sees something they like that they intend to purchase, they could now simply put it in their purse or backpack or pocket, and walk out.

When they do so—thereby crossing the threshold of what the patent calls the “transition area”—the sensors will compile the list of what the consumer—what the patent calls a “user”—has picked out, and send that itemized list to the user, via email or some other notification, along with all pricing information.

Simultaneously, the system would bill the user’s account directly, so that no cash/card exchange would be needed.

Says the patent application, “User information may include, but is not limited to, user-identifying information (e.g., images of the user, height of the user, weight of the user), a user name and password, user biometrics, purchase history, payment instrument information (e.g., credit card, debit card, check card), purchase limits, and the like.”

If your eye muscles twitched a bit in reading that last paragraph, you’re not alone.

The ramifications of stores like these implicate many privacy concerns that have detracted from some of the optimism.

One reading of the application is that everyone who enters this store will have photos snapped of them by the scores, without any indication as to whether (or where) they’ll be stored, or to what purpose they might be put after the transaction has been completed.

Another plausible reading is that no “opt-in” or registration scheme would be necessary, meaning that everyone is automatically eligible to use these stores. And while that could be viewed as good and efficient to some, to others it means unparalleled access to bank accounts, IDs, and other personal information the likes of which have never been seen outside of science fiction.

There are concerns, too, in the logistics. If a retail store is extremely busy on a given day—say, around the holidays—will the cameras and sensors be adequately equipped for that kind of traffic? What happens when the system makes a mistake, and charges a “user” for too many items? Or the wrong items? (For instance, if it charges the user for buying the name brand when in fact they chose the less expensive generic.) What about when the system simply charges the wrong “user” altogether?

Many of those issues arguably could be solved with a call to customer service, but if the mistakes are frequent, then wouldn’t that negate the purpose of this system entirely, by forcing consumers to interact with personnel after all and reintroducing the “headache” that this patent specifically aims to avoid? Moreover, how will this system deal with those who inevitably try to subvert it by wearing hats or hoods?

Of course, in all of this, it’s important to keep in mind that just because a patent is issued doesn’t necessarily mean that the contents of that patent will ever materialize.

Large companies like Amazon have huge intellectual property profiles; companies with big IP profiles apply for lots of patents, and many of them never end up in the market.

So why does Amazon even want a brick-and-mortar presence in the first place, when the trend seems to suggest that the average (American, at least) consumer is preferring more and more the ease of e-commerce?

One reason may be that Amazon is attempting to emulate Apple’s business success, through sales of such things as original smart phones and tablets, but, while Apple has physical stores where potential customers can go and lay their hands on the product and play with it, no such equivalent exists for a Kindle.

There are three credited inventors of Amazon’s new scanning system: Steve Kessel (who led the team that helmed the Kindle), Dilip Kumar, and Gianna Puerini.

There is also a second patent issued recently to Amazon for a system of kiosks that Amazon could spread out across tens of thousands of gas stations, airports, and malls. This kiosk system would allow purchasers to order a product online and specify a nearby kiosk from which they would like to pick it up immediately.

The concept would decrease shipping costs for the retailer and consumer (making it potentially free for the consumer), and would work largely by pre-stocking items that Amazon anticipates will be popular sells.

So, while some of Amazon’s plans for physical storefronts haven’t quite materialized yet, don’t be surprised if these designs begin to emerge in the near future.