by Jonathan Schmig

March 30, 2015

The U.S. Patent Office has just issued Apple a new patent over a process that let’s you track another person’s journey.

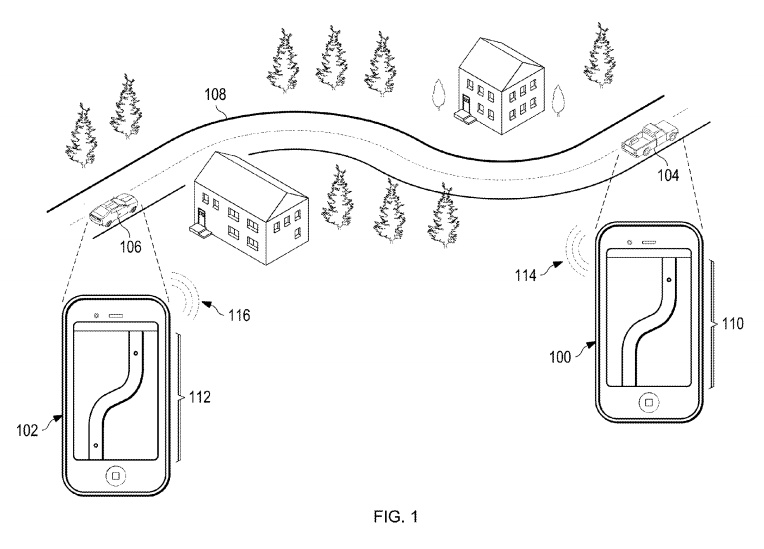

Apple already has a feature that lets you find your friend (or spouse or child or whomever); the innovation of this new process is that the data transmitted is not confined to just the single spot the friend is currently occupying, but instead the data includes potentially the entire route your friend took to get there.

Using GPS technology, this “people tracker” plots points of your journey from the time you activate the feature (turn it on, open the app, etc.) to the time you turn it off. The patent claim itself (available here) lays out a series of potential uses for the function.

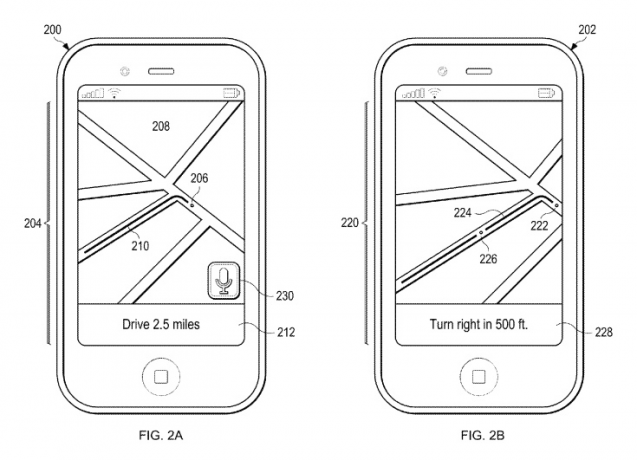

For instance, if you’re driving to a destination, and your friend is following you in a different car, you can both activate this feature and in doing so send your friend the path you’ve taken/are taking so they can follow. Or, if you have the directions pulled up on your phone but they don’t, you can both enter a “mirroring mode,” whereby your friend’s device shows exactly what your device is displaying.

Via U.S. Patent & Trademark Office

But its use would not be limited to, say, cars: “Either or both of the devices could be carried by a human being on foot, or an animal, or a robot.” So a concerned parent might use the app to monitor their child driving home from school; a hiker might use the app to more meet up with their friend; a pet-owner might affix the tracker to their dog; an army official might tack it onto a robot before sending it into a hazardous area.

As a patented “process,” this feature is not limited to any one embodiment. That is, it could and (almost certainly would) appear as an app in your smartphone, but, according to the patent claim itself, the tracker could also appear in really “any kind of electronic device, e.g., a laptop computer, a tablet computer, a wrist-mounted computer, a personal digital assistant, a built-in navigation system (e.g., built into either or both of the automobiles), or any other kind of device capable of transmitting and receiving information.” The GPS could be accessed using mobile data, or WiFi, or Bluetooth.

Also, crucially, the device itself (whether phone or laptop or tablet or watch) need not match the second device—for example, as the claim explains, “one device could be a smartphone and the other device could be a laptop computer.” Since the patent covers a process and not a specific thing, this makes sense. And anyone who’s ever received a phone call on their computer knows this isn’t new.

Additionally, the connection or transfer would not be limited to just two devices. The examples that the patent claim adopts mostly (for simplicity’s sake) address just two users, but the patent also hastens to point out that multiple devices could all hook up to the same feed (the “conference call” of people tracking, in a way). The first device could enter “broadcast mode,” in which case the device’s location and path are simply shared with… well, any number of other devices.

Alternatively, the first device “may make this information publicly available, e.g., in a database or other resource available to many other users of mobile devices.” The hiker may choose, therefore, to simply send the information to the cloud, or to Facebook, where people who are not explicitly designated by that hiker may nevertheless access the information (perhaps after limiting the group’s pool, for example by only letting “Facebook friends” see it).

Via U.S. Patent & Trademark Office

This, though, raises an important question, probably the first thing you thought of when you read this article’s headline: privacy. As AppleInsider put it, “Path tracking, or recording multiple points along a given route, has been a tentpole GPS feature since the early days of portable systems. Certain apps support such functionality, but most mainstream solutions eschew the data, due in part to privacy concerns.”

Now, Apple has explicitly promised at least one major (and obvious) safeguard, and that is essentially an opt-in policy. You can’t just look up your friend’s location data whenever you feel like it without them knowing; you must send them a request (via email, text, notification, etc.), and they must accept. Only then is information transferred.

This request feature may also come with a location disclosure caveat, meaning whoever is the one requesting the link may be forced (or asked) to reveal their location first—so that the requestee can see the location of the requesting party before they decide whether or not to accept. (If, for instance, they only want to share information with people physically nearby.)

The request could also implement a facial identification feature, so that the requestee can see a picture of the person sending the request (to verify that it really is their friend who is using their friend’s phone, e.g.).

But that doesn’t necessarily mean privacy won’t be an issue. Recently, major companies (like Apple, and like Facebook) have come under some scrutiny for their privacy and data collection policies. Facebook, famously (or infamously), requires a registrant to confer the company with rights over every single photo that registrant may post on their profile.

Since most people don’t even read the terms and conditions when they sign up, many don’t realize that any picture that includes them and that is uploaded to Facebook, no matter who posted it or how quickly it was removed, is legally Facebook’s, and they can do what they want with it. Apple, too, has been criticized recently, like when the public found out their operating system was automatically sending to Apple all sorts of information, including their locations and search queries.

Via U.S. Patent & Trademark Office

So, simply put, if Apple decides to put a term like that in their terms and conditions, then theoretically your location data could be accessed by people without your consent (because, the theory goes, you actually already gave your consent by signing up). If Apple wants to see where you’ve been, they could do so.

Conceivably, that right could be extended to other parties as well (read: law enforcement). Simply having the app on your phone, even if you’ve never used it once, or even if the only time you do use it is to track your dog, would enable an inquiry into everywhere the device has been—whether it’s attached to your car, or it’s in your pocket, or anything else.

For instance, in the example where the first user enters “broadcast mode,” the patent explicitly states that that device perhaps “may not receive any communications from other devices and may not be notified that other devices are receiving location information.” In the immediate sense, this is straightforward: if you activate “broadcast mode,” then you know you are simply making that information public.

But the point is that there are any number of ways that function (accessing someone’s location data without informing that person’s device, and by extension the person) could be manipulated or mishandled. With great potential, comes potentially great abuse.

As it stands, there is not yet a commercial embodiment, nor is there any specific plan by Apple to implement the subject of this new patent. Many patents are issued, but not all of them mature into use, so it’s possible that this technology never actually hits the market.

But, given the fact that Apple already has their “find my friend” feature out there, and given Apple’s financial capability to handle such a feat, this “people tracker” seems pretty likely to materialize.